Parque del Pasatiempo: Sustainable Education in Ruins

By Ellis Dixon

Betanzos, Spain

Exit Highway N-VI Rúa Fraga Iribarne at Rúa Instituto Francisco Aguiar

I stood in the midst of a full-on dragon fight in the middle of a public park. A winged beast with sharp teeth snapped at another who cheekily stuck out his forked tongue in defiance. Ducklings fled the scene into nearby caves and I wondered if it was because of the mythical brawl or simply my presence.

Located in Betanzos, a town in Spain’s northern Galicia with a population of 13,000, this mostly abandoned park was the opposite of sustainable to the naked eye. It’s a park built at the turn of the century with imported materials, using imported plants and animals and, at one point, maintained through the use of an incredible amount of water and power. And now, monsters were looking to be fed.

In 1914, founders Juan and Jésus García Naveira opened Parque del Pasatiempo to the public after eight long years of construction. It wasn’t their only contribution to their hometown, which they had left to make their fortunes in South America. The Naveiras had also erected a school, a washroom, and public plaza in the center of town.

But Pasatiempo was more of a vanity project of sorts, albeit with an educational goal in mind. It was designed as an encyclopedic theme park whose mission was to show the population the wonders of the world the brothers Naveira claimed to have seen on their adventures, though the history books say they were almost entirely based in Argentina while amassing their wealth.

Pasatiempo was intended to promote a broader worldview to people without a functioning library or any means to travel. The 90,000 square meter grounds were converted into an interactive sculpture garden that celebrated education and human achievement. This was the closest most of the inhabitants of Betanzos would ever come to the Great Wall, the Panama Canal, a mosque, or the great pyramids of Cairo, all neatly displayed for them in their own modernist style.

Sadly, after the death of Juan in 1933, over 90% of the park was lost to redevelopment, wars (it was used as a concentration camp in the Spanish Civil War) and, of course, theft. Originally there was a zoo, an avenue of the emperors, a garden celebrating great literary minds with Edward Scissorhands-style hedges shaped into table and chairs resembling modern-day corporate conference rooms, and even a statue of Jesus, underneath which a sign labeled him as the first socialist. Reportedly, there was even a stone harem full of naked dancing women, positioned precariously close to a walkway flanked with busts of the popes. In later, more puritanical years, you can imagine which spectacles were the first to go.

And so the park was abandoned, left to the elements for almost half a century. It wasn’t until the mid-1980s that the town of Betanzos began reclaiming it from the brush of wild vines. Now you can visit the parts that remain: a wonderland forgotten by time and visited by few. The one thing that remains untouched is its unorthodox approach to sustainable education.

A circular maze of hedges surrounding four stone pylons caught my attention first. It took me from the small two-lane road where I left my car and led me to a modern iron pedestrian bridge that crossed over the main street. On the other side, I could make out a series of chipped-stone and weathered marble terraces peeking out between weed-catching cracks, framed by grand stone staircases on either side.

No ticket booth separated me from my find, no tour guides approached me, no one seemed to be around at all. I was alone but for the birds heckling me from their posts in the gnarled oak trees. In my discovery I felt as giddy as Mary Lennox, but my secret garden happened to be hiding in plain sight, and I wasn’t certain whether I was trespassing.

Once on the other side of the bridge, I entered the first terrace, which sat above a completely shell-tiled pond surrounded by dripping grottoes and covered in a blanket of thin green algae. In the center stood a cupola housing two formerly whole bathing nymphs. Just left of the grand staircase leading to the pond was a brightly painted underwater explorer in his turn-of-the-century diving gear uncovering buried treasure as he popped out of the wall.

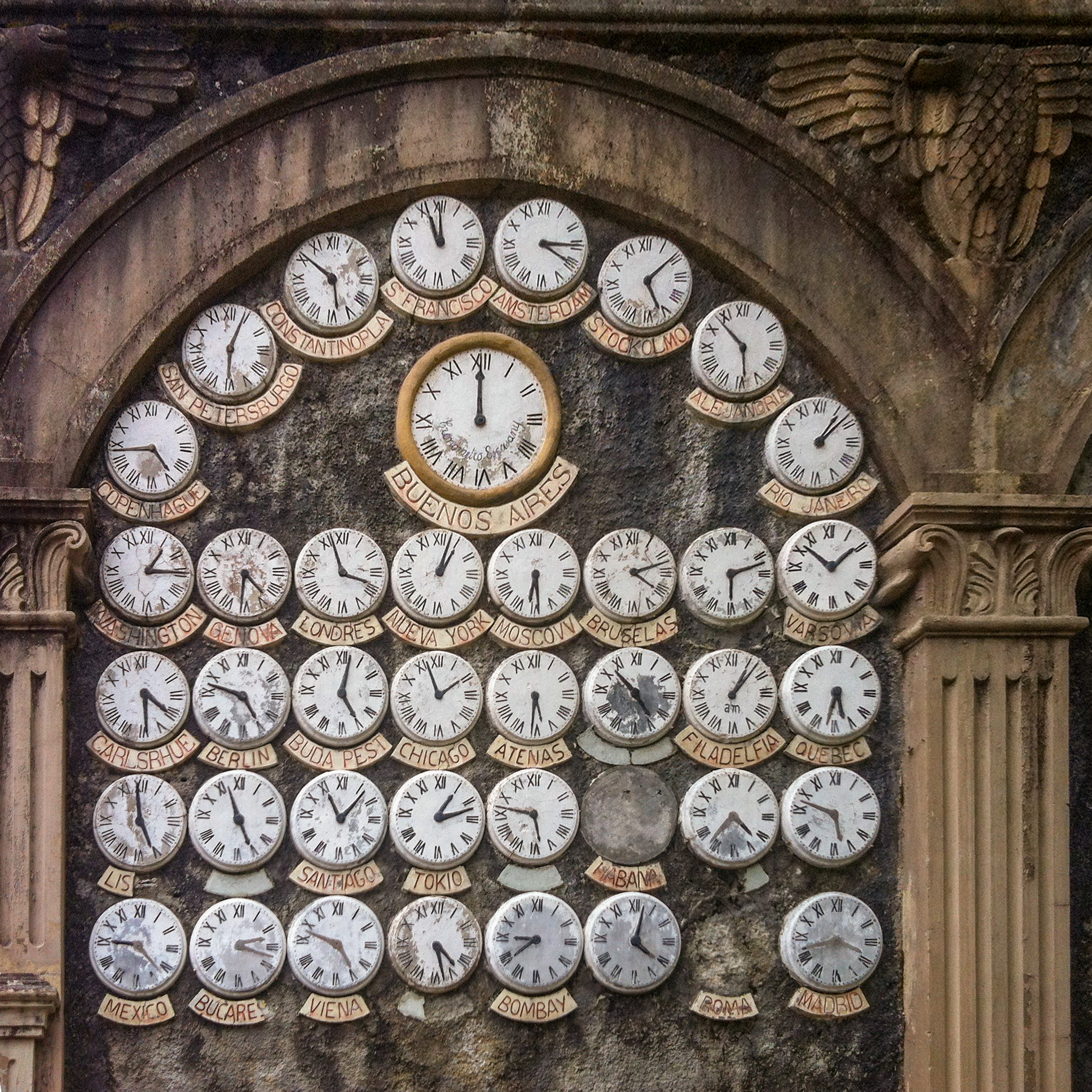

One level up was a wall of cement and ceramic clocks set to different time zones: Constantinople, St. Petersburg, San Francisco, a dozen of them or more. The largest of the clocks was Buenos Aires, forever set to high noon. To the left, a wall read, Hijas Republicanas de España, (the Republican sons of Spain). Eighteen ceramic tiles affixed under the heading represented the crests of Spanish-speaking countries in Central and South America from Mexico to Argentina. Strangely enough, a crest of Brazil was included. Perhaps it was meant to be a red herring, but no one knows for sure.

To the right of the clocks, a camel caravan through the Sahara invited me to follow them through an arch decorated as the Mezquita Mohammed Ali Mosque and into a cave. Inside were strange prehistoric monsters, overgrown lizards, and giant creepy-crawlers hiding between the rocks and hanging from the ceiling. A deep well with a nearby hidden entrance to the bottom sat in the middle, with a trickling flow of water at its base and years of moss growing around the inside.

Over my shoulder were four narrow exits to the next tier up, each one leading to a different viewpoint: an iron gazebo, a circle of stone benches, the remains of a flower garden, and a limbless female statue guarding a patch of grass. Following any of these paths led to a giant stone lion who seemed to be in charge of it all. Modern-day vandals have had a field day with the lion’s anatomical correctness, but don’t let that bother you. It doesn’t seem to make a difference to him.

Leaving Pasatiempo, I thought, if at the turn of the century we can create a palpable connection between the people of a small village to the world at large, then we can certainly achieve a similar result today. Through education, we can remove fear of the unknown from our rhetoric. It all starts with opening our eyes and celebrating our differences. The rest should be a walk in the park.

Avenida Castilla, 38

15300 Betanzos A Coruña

Spain

Recommended Hotel:

Hotel Palacete de Betanzos

Stay in this reconstructed, turn-of-the-century house of the Naveira brothers. Easy walking distance from the central square and situated right along the Camino Ingles (the English Way) of the Camino de Santiago de Compostela. Pilgrims get a 10% discount with their credentials.

Ellis Dixon is the founder of AtlasLisboa.com, a blog that focuses on the hidden side of Lisbon, Portugal.